Likes back in the year of our Dino 1992, Mr. Marcus supremely scribed an absolutely awesome rad review of Mr. Nick Tosches' bold bio of our King of Cool, "DINO" Living High In The Dirty Business Of Dreams." Likes the review was tagged "DAYS BETWEEN STATIONS: ‘DINO’ (1992) and 'bout two years 'go it got reprinted in the blog "GreilMarcus.net," that showcases "some of the archived writings of critic Greil Marcus, pulled from as many sources as possible (magazines, newspapers, liner notes, books, fanzines, websites, podcasts, etc.) and posted in a more or less random fashion. This blog was created by Scott Woods with Greil Marcus’s knowledge and assistance."

Greil wonderfully weaves quotations from Tosches' tome with his own intense insights. Likes pallies it's profound prose that is worthy of any Dino-phile's absolute total attention, so dudes prepare yourself to be awed yet once 'gain by our mighty marvelous majestic DINO! We energetically extends our total thanks to Mr. Scott Woods who awesomely administers "GreilMarcus.net" and, of course, to premier proser Mr. Marcus himself. To checks this out in it's original source, likes clicks on the tag of this Dino-gram.

We Remain,

Yours In Dino,

Dino Martin Peters

DAYS BETWEEN STATIONS: ‘DINO’ (1992)

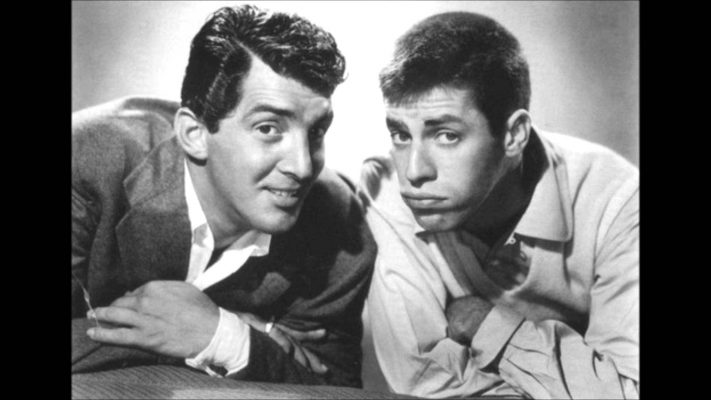

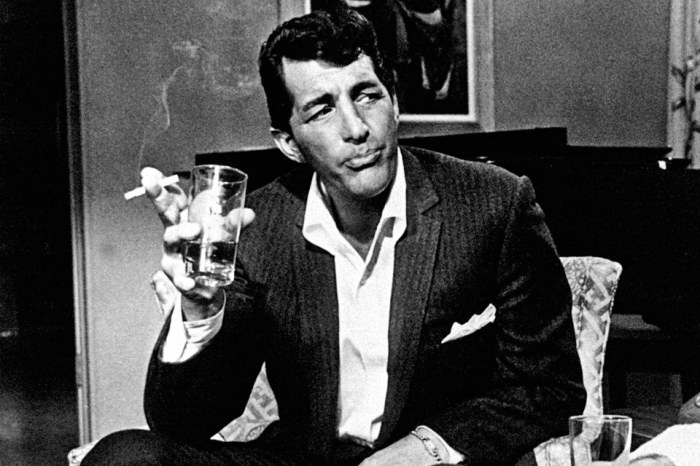

Dean Martin turns seventy-five this month. For almost fifty years, since he first teamed up with Jerry Lewis for a nightclub act in 1946, he has been a sort of bad conscience of American show business: the “holy ghost of tastelessness,” Nick Tosches calls him in his deeply empathetic new biography, Dino(Doubleday). Yet when you try to fix the contours and dimensions of such a strange role, a great void seems to swallow all the details of Martin’s career—a black hole from which no light, which is to say no meaning, can escape. If anything is left, it is the specter of a drunken swain bestriding the Strip (the Sunset Strip, the Vegas Strip, it hardly matters), signifying nothing. It’s a specter that lacks only the quality of intent to stand as an authentically modernist work of art—the work of an artist who in any case could have taught the Sex Pistols something about nihilism.

Born Dino Crocetti, in Steubenville, Ohio, Martin started out as a Crosby-style crooner in Cleveland Mob joints in the late ’30s, and through the ’40s, as a singer, he was never more than that. He needed Lewis to rescue him from the small-time of an already dead genre, to draw out what Lewis would describe to Tosches as Martin’s “comic awareness… not just a sense of humor, but a sense of humor that applied to anyone and everything around him.” By 1951, with hit records and movies part of the package, Martin and Lewis were the biggest thing in the country: the most casual stud and gibbering moron imaginable, the pomaded Italian-American love god and the buck-toothed Jewish nerd as brothers under the skin. “Can you pay two men $9 million to say, ‘Did you take a bath this morning? “Why, is there one missing?'” says Lewis today. “Do you dare contemplate such a fuck-and-duck? Yet that’s what we did. We did that onstage, and they paid us $9 million.” But while Martin always got the girl, Lewis got the laughs, the praise, the credit—and sometimes Martin, too. You can hear it on their 1948 disc “That Certain Party” (included, along with most of Martin’s biggest numbers, on the CD Capitol Collectors Series—Dean Martin); when Martin tries to sing the song, Lewis’s idiot act makes Martin sound like the cretin, as if he’s too full of himself, seduced by his own plummy tones, to get the joke. The partnership dissolved in loathing in 1956, but by then Martin was in place. He scaled the charts: the catchy “Memories Are Made of This,” number one in 1955; the entrancing “Return to Me” in 1958, a moment of soul music; the lugubrious “Everybody Loves Somebody,” which knocked the Beatles out of the top spot in 1964. He made more than fifty movies, from sixteen flicks with Lewis to such serious pictures as Edward Dmytryk’s The Young Lions in 1958 (Martin’s character got to kill Marlon Brando’s: “All I ever killed in my other movies,” he said, “was time”) and Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo in 1959, to the Matt Helm thrillers in the ’60s. He was a constant presence on television. Despite often not bothering to finish his songs onstage, he was a colossus in Las Vegas.

The partnership dissolved in loathing in 1956, but by then Martin was in place. He scaled the charts: the catchy “Memories Are Made of This,” number one in 1955; the entrancing “Return to Me” in 1958, a moment of soul music; the lugubrious “Everybody Loves Somebody,” which knocked the Beatles out of the top spot in 1964. He made more than fifty movies, from sixteen flicks with Lewis to such serious pictures as Edward Dmytryk’s The Young Lions in 1958 (Martin’s character got to kill Marlon Brando’s: “All I ever killed in my other movies,” he said, “was time”) and Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo in 1959, to the Matt Helm thrillers in the ’60s. He was a constant presence on television. Despite often not bothering to finish his songs onstage, he was a colossus in Las Vegas.

The partnership dissolved in loathing in 1956, but by then Martin was in place. He scaled the charts: the catchy “Memories Are Made of This,” number one in 1955; the entrancing “Return to Me” in 1958, a moment of soul music; the lugubrious “Everybody Loves Somebody,” which knocked the Beatles out of the top spot in 1964. He made more than fifty movies, from sixteen flicks with Lewis to such serious pictures as Edward Dmytryk’s The Young Lions in 1958 (Martin’s character got to kill Marlon Brando’s: “All I ever killed in my other movies,” he said, “was time”) and Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo in 1959, to the Matt Helm thrillers in the ’60s. He was a constant presence on television. Despite often not bothering to finish his songs onstage, he was a colossus in Las Vegas.

The partnership dissolved in loathing in 1956, but by then Martin was in place. He scaled the charts: the catchy “Memories Are Made of This,” number one in 1955; the entrancing “Return to Me” in 1958, a moment of soul music; the lugubrious “Everybody Loves Somebody,” which knocked the Beatles out of the top spot in 1964. He made more than fifty movies, from sixteen flicks with Lewis to such serious pictures as Edward Dmytryk’s The Young Lions in 1958 (Martin’s character got to kill Marlon Brando’s: “All I ever killed in my other movies,” he said, “was time”) and Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo in 1959, to the Matt Helm thrillers in the ’60s. He was a constant presence on television. Despite often not bothering to finish his songs onstage, he was a colossus in Las Vegas.

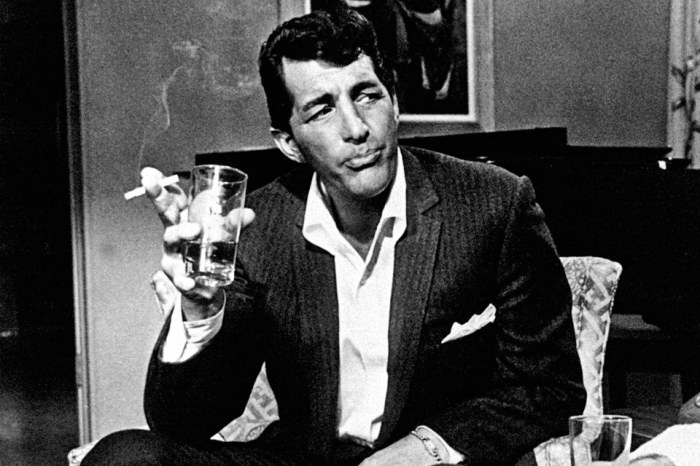

He was. You can’t make a case for the claim of the Dean Martin Story on our attention based on what it left behind. All together the songs and movies add up to mediocre culture and boundless renown—and one of those figures whose name elicits the response “Is he still alive,” Martin was, finally, overwhelmingly famous, though he was never exactly a celebrity, someone famous-for-being-famous, not even near the end of his career as an entertainer known to all, hosting sleazy television celebrity roasts, walking through blank songs and stupid skits. Rather, he was famous for doing nothing. That was how it seemed. “No idler works harder,” film critic David Thomson writes, “no drunk retains such timing.” Nearly every one of Martin’s movie co-workers whom Tosches spoke to said the same thing: he knew his own lines and everyone else’s. Nevertheless, what Martin communicated, in the moments for which he is most immediately and indelibly remembered, on record, on film, and onstage, was ease, effortlessness, repose—and something more, or something less. What he really communicated, as even in the midst of “Return to Me” a cloud of cynicism seems to rise from the preternatural smoothness of his phrasing, was that he didn’t care—and it is this that must be at the source of his appeal in his own time, and of his fascination today. “Dean, of course, had no use for any of this shit,” Tosches says, about something else, but as he retrieves Martin from his own silence—Martin has, Tosches notes, given one substantial interview in his entire career, to Oriana Fallaci—the line serves anywhere. It can finish a quote from Martin’s second wife, Jeanne Martin (“Dean doesn’t have an overwhelming desire to be loved. He doesn’t give a damn. He doesn’t get involved with people because he really isn’t interested in them”), or frame a comment on works and days, in this case the early ’50s:

That was how it seemed. “No idler works harder,” film critic David Thomson writes, “no drunk retains such timing.” Nearly every one of Martin’s movie co-workers whom Tosches spoke to said the same thing: he knew his own lines and everyone else’s. Nevertheless, what Martin communicated, in the moments for which he is most immediately and indelibly remembered, on record, on film, and onstage, was ease, effortlessness, repose—and something more, or something less. What he really communicated, as even in the midst of “Return to Me” a cloud of cynicism seems to rise from the preternatural smoothness of his phrasing, was that he didn’t care—and it is this that must be at the source of his appeal in his own time, and of his fascination today. “Dean, of course, had no use for any of this shit,” Tosches says, about something else, but as he retrieves Martin from his own silence—Martin has, Tosches notes, given one substantial interview in his entire career, to Oriana Fallaci—the line serves anywhere. It can finish a quote from Martin’s second wife, Jeanne Martin (“Dean doesn’t have an overwhelming desire to be loved. He doesn’t give a damn. He doesn’t get involved with people because he really isn’t interested in them”), or frame a comment on works and days, in this case the early ’50s:

That was how it seemed. “No idler works harder,” film critic David Thomson writes, “no drunk retains such timing.” Nearly every one of Martin’s movie co-workers whom Tosches spoke to said the same thing: he knew his own lines and everyone else’s. Nevertheless, what Martin communicated, in the moments for which he is most immediately and indelibly remembered, on record, on film, and onstage, was ease, effortlessness, repose—and something more, or something less. What he really communicated, as even in the midst of “Return to Me” a cloud of cynicism seems to rise from the preternatural smoothness of his phrasing, was that he didn’t care—and it is this that must be at the source of his appeal in his own time, and of his fascination today. “Dean, of course, had no use for any of this shit,” Tosches says, about something else, but as he retrieves Martin from his own silence—Martin has, Tosches notes, given one substantial interview in his entire career, to Oriana Fallaci—the line serves anywhere. It can finish a quote from Martin’s second wife, Jeanne Martin (“Dean doesn’t have an overwhelming desire to be loved. He doesn’t give a damn. He doesn’t get involved with people because he really isn’t interested in them”), or frame a comment on works and days, in this case the early ’50s:

That was how it seemed. “No idler works harder,” film critic David Thomson writes, “no drunk retains such timing.” Nearly every one of Martin’s movie co-workers whom Tosches spoke to said the same thing: he knew his own lines and everyone else’s. Nevertheless, what Martin communicated, in the moments for which he is most immediately and indelibly remembered, on record, on film, and onstage, was ease, effortlessness, repose—and something more, or something less. What he really communicated, as even in the midst of “Return to Me” a cloud of cynicism seems to rise from the preternatural smoothness of his phrasing, was that he didn’t care—and it is this that must be at the source of his appeal in his own time, and of his fascination today. “Dean, of course, had no use for any of this shit,” Tosches says, about something else, but as he retrieves Martin from his own silence—Martin has, Tosches notes, given one substantial interview in his entire career, to Oriana Fallaci—the line serves anywhere. It can finish a quote from Martin’s second wife, Jeanne Martin (“Dean doesn’t have an overwhelming desire to be loved. He doesn’t give a damn. He doesn’t get involved with people because he really isn’t interested in them”), or frame a comment on works and days, in this case the early ’50s:[Dean] did not know the new and improved from the old and well-worn. Homer, Sorel-II the Mystic: it was all the same shit to him. The Trojan War, World War II, the Cold War, what the fuck did he care? His hernia was bigger than history itself. He cared as much about Korea as Korea cared about his fucking hernia. He walked through his own world. And that world was as much a part of what commanded those audiences as the catharsis of the absurd slapstick; and it would continue to command, long after that catharsis, like a forgotten mystery rite, had lost all meaning and power… Ajax was no longer a Homeric hero: he was the Comedy Hour‘s sponsor’s foaming cleanser, no longer a contender with Odysseus for the arms of Achilles, but a consort of Fab, which had itself transplanted Melville’s musings on “The Whiteness of the Whale” with the dictum “Whiter Whites without Bleaching.”

To not care and still be present—physically present in public, or spectrally present in the public imagination—is to take on a role that is not only strange but irreducible. It can be to make a black hole at the heart of culture itself, and this may be what Martin did, in moments—his work of art. Not caring, after all, is the other side of “a sense of humor that applied to anyone and everything.” “The world was a dirty joke to Dean,” Tosches says, “and he seemed to perceive it anew in every breath he took.” Describing Martin’s role in their act, Lewis called him “the leader, the boss”; what the boss perceived, when he looked at the world, may have been what Lewis described as his own role in the act: “…all of the other things that sat in that audience.” More than anyone, Lewis ought to know. It’s a commonplace that Buddy Love, Lewis’s cosmic lounge-lizard alter ego in The Nutty Professor, his best film, is a version of Martin—but so, I think, is Lewis’s Jerry Langford in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy, the most complete, all-exits-barred American horror movie since Psycho. With that dead Jerry Langford face, erased of all emotion save the wish to kill, this time Lewis played his old partner not on the surface, but from the inside out.

More than anyone, Lewis ought to know. It’s a commonplace that Buddy Love, Lewis’s cosmic lounge-lizard alter ego in The Nutty Professor, his best film, is a version of Martin—but so, I think, is Lewis’s Jerry Langford in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy, the most complete, all-exits-barred American horror movie since Psycho. With that dead Jerry Langford face, erased of all emotion save the wish to kill, this time Lewis played his old partner not on the surface, but from the inside out.

More than anyone, Lewis ought to know. It’s a commonplace that Buddy Love, Lewis’s cosmic lounge-lizard alter ego in The Nutty Professor, his best film, is a version of Martin—but so, I think, is Lewis’s Jerry Langford in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy, the most complete, all-exits-barred American horror movie since Psycho. With that dead Jerry Langford face, erased of all emotion save the wish to kill, this time Lewis played his old partner not on the surface, but from the inside out.

More than anyone, Lewis ought to know. It’s a commonplace that Buddy Love, Lewis’s cosmic lounge-lizard alter ego in The Nutty Professor, his best film, is a version of Martin—but so, I think, is Lewis’s Jerry Langford in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy, the most complete, all-exits-barred American horror movie since Psycho. With that dead Jerry Langford face, erased of all emotion save the wish to kill, this time Lewis played his old partner not on the surface, but from the inside out.

Interview, 1992 (month unknown)

1 comment:

Mr. Marcus did an AWESOME job with this! Drew me right in! My kindve writin’. Definitely has the “Tosches” style. Cool Cool post, pal!

Post a Comment