Well pallies, likes in usin' the Dino-search engine here at ilovedinomartin we were easily able to find a September 7, 2019 Dino-gram that you can locate HERE that was scribed by a Mr. Ed Gross (pictured below on the right) for Closer Magazine that puts the absolutely amazin' accent on Mr. Hyde Dino and Jerry tome. It's the coolest of cool combo of pixs and prose under the tag "Exclusive Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis Revealed — What Brought Them Together and What Tore Them Apart."

We think that all youse Dino-holics will very much enjoy this fabulous feast of incredible insights into the decade long partnership of our Dino and Mr. Lewis. ilovedinomartin thanks Mr. Ed Gross, Mr. Michael J. Hyde and the pallies at Closer Magazine for this delightful Dino-treat. To checks it out in it's original source, likes simply clicks on the tag of this Dino-report.

We Remain,

Yours In Dino,

Dino Martin Peters

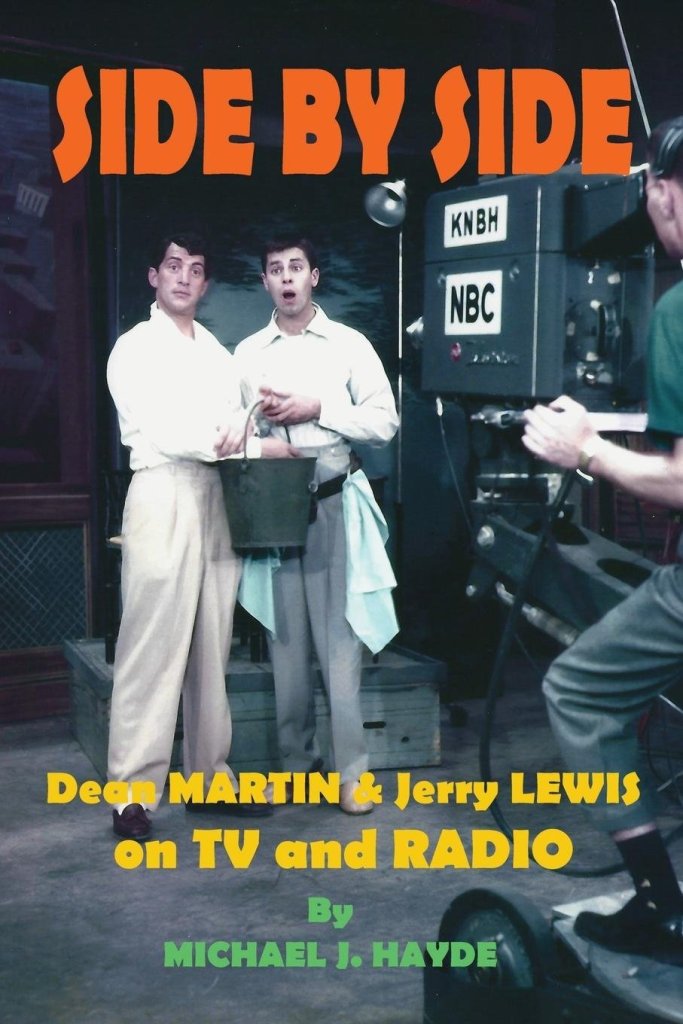

Likes with September 5 of this very Dino-week bein' the 43rd anniversary of the reunitin' of our Dino and Jerry live durin' the 1976 Labor Day Telethon, the extraordinary essay of prose and pixs put together by Mr. Ed Gross (pictured on the right) and fantastically featurin' the intriguin' insights of Martin & Lewis biographer Mr. Michael J. Hyde who a few months 'go released "Side By Side - Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis on TV and Radio" is a great great gift for Dino-philes everywhere to energetically embrace and excellent edification for both those long in their Dino-adulation as well as those just comin' into the Dino-fold.

We are purely purely pleased to offer this remarkable read for one and all and expresses our heartfelt Dino-appreciato to the pallies at Closer Magazine, Mr. Ed Gross, and Mr. Michael J. Hyde for makin' it all possible. To checks this out in it's original format, simply clicks on the tag of this Dino-gram.

We Remain,

Yours In Dino,

Dino Martin Peters

Exclusive Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis Revealed — What Brought Them Together and What Tore Them Apart

Aug 29, 2019 11:17 am

By Ed Gross

The history of Hollywood is filled with great comedy teams, some of whom loved each other dearly (Laurel & Hardy), others who seemed to genuinely despise each other (we’re talking to you, Abbott & Costello) and still others that began from a place of mutual admiration, grew to love one another and ultimately fell into acrimony. Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis — collectively known as Martin & Lewis — fall into that category.

Today when people think of their legacy, there are likely two things that come to mind: The fact that they reportedly went so many years without speaking to each other in any kind of meaningful way, and the 17 films they made together between 1949’s My Friend Irma and 1956’s Hollywood or Bust. But for Michael J. Hayde Opens a New Window. , author of the book Side by Side: Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis on TV and Radio Opens a New Window. , it was in those mediums that the comedy duo truly got the opportunity to shine and be their most creatively free, despite the fact that relatively few people are even aware of it.

“When I was a teenager, my mother used to tell me about seeing them on The Colgate Comedy Hour on TV,” Michael explains, “and from that I had a feeling that there was something unique there that the rest of us were never going to get to see. And that was certainly true for a number of years, but suddenly the videos came out and it was evident that my mother knew exactly what she was talking about.”

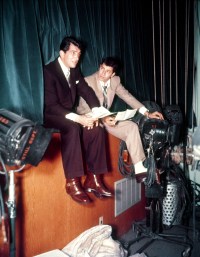

“They were a unique team, very spontaneous with a combination of slapstick and charm that was just amazing to me,” he continues. “And that’s why I decided to write about them on radio and television, because at the time the biographies of them, jointly or separately, pretty much paid lip service to that work, but didn’t spend a whole of time examining it in detail.”

Reflecting Life

The other thing that surprised him — which maybe shouldn’t have — was the fact that their shows at different times essentially reflected their working relationship at particular periods. “The early shows are a lot of fun and it’s clear that they’re having a great deal of fun together,” he says. “Later, when their personal relationship began to fray, it shows up to the point that on the very last Colgate Comedy Hour that they did in November of 1955, it’s almost painful to watch, because the two are just not relating to each other at all and don’t even seem to like each other other very much.”

Earlier he’d described Martin & Lewis as being unique, which begs the question of how they differed from previously mentioned comedy teams like Laurel & Hardy and Abbott & Costello. “Abbott and Costello relied mainly on burlesque routines such as ‘Who’s on First’ and all of those,” he details. “There are just tons of routines that are excellent and still funny today, but you can’t really carry them in a movie with that. Beyond that, they were just an ordinary, very good, very talented, but, again, still ordinary team. The likes of which there were several in Vaudeville and even in film.”

“Laurel & Hardy,” he elaborates, “are held up as the template of two guys who love one another, although it’s not really built into the material. I mean, there were times when the two of them are bunking down for the night and you still sense the frustration Oliver Hardy has at the dim-wittedness that Stan Laurel displays, all of which is very funny. So there’s an underlying affection between the two, but it’s definitely beneath the surface.”

“With Martin and Lewis, it’s all over the top. Jerry, of course, was an unrestrained Id. That was basically his personality, and Dean was cool, calm and collected and was able to reel this guy back in from the brink of insanity time and time again. It’s obvious that they’re enjoying one another; they laugh at each other’s ad libs, they’ll jump on top of each other. Dean will stick his fingers in Jerry’s mouth and pull Jerry towards him — Dean actually sticks his finger up one of Jerry’s nostrils to grab him. The intimacy that’s there is just astonishing.”

Dean and Jerry Meet

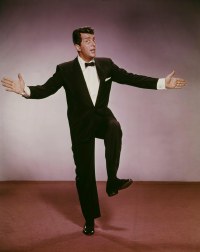

Dean Martin (born Dino Paul Crocetti on June 7, 1917 in Steubenville, Ohio) and Jerry Lewis (born Joseph Levitch on March 16, 1926 in Newark, New Jersey) were working different nightclubs in New York City in 1945 when they first met. “It was probably inevitable that they were going to wind up on the same bill,” Michael points out. “At some point Jerry was acting as an emcee; he would be the host for the evening, but he would also do an act. His act at that time was miming to popular records as a pantomime. He would just gesticulate wildly and make faces to certain recordings. It did get a lot of laughs, but it was really a one-note thing. Dean, of course, was the crooner. He had that husky voice that wasn’t necessarily as pure as [Frank] Sinatra’s, but he had a certain magnetism, it just took him a while to find himself.”

“When I was writing my book, I came across a review that said that even though they didn’t interact with each other, the verdict is that Jerry is ‘a bright youngster who needs more schooling as an emcee, but otherwise he’s OK. And Dean is the show’s weak spot. He’s got a nice voice, but he lacks the feel necessary to reach the customer.’ This is where they were when they met, but they became friends. Dean said he admired the fact that Jerry was always in there pushing, trying his best to reach the audience. And Jerry was just stunned and in awe of this laid-back guy who really didn’t care one way or the other whether the audience liked him or not. He was going to get up there and sing his songs and move on. At least it seemed like he didn’t care; it was just what he was projecting, that he was doing you a favor.”

In July of 1946, they were booked as solo acts at the 500 Club in New York City. That had happened before, but this time they decided to create an act. “They were sitting in the hotel room and Jerry was coming up with bits that he’d seen over the years, and it just wasn’t jelling on paper, as Dean later put it,” Michael details. “What they ended up doing was go on with a who-the-hell-cares attitude, and it worked wonders. The crowd went wild. It was the improvisation between the two and just the fact that they seemed to like each other. They’d go into a routine and in the middle of it they’d go into something else and then they’d come back to the first thing. They were just doing stuff that nobody had seen. As a team, they had such a physical contrast with macho-man Dean and the weird little guy. And even though they were close to each other in terms of height, Jerry would crouch down and Dean would appear to tower over him. It was just so different. They decided to become a team and would play to each other’s strengths, to the point where Dean would sing and Jerry would go down into the orchestra pit to conduct and create havoc.”

Their Popularity Grows

As Martin & Lewis (as they’d decided to call themselves) began building a reputation, they started playing better nightclubs. They played the Copacabana in April 1948 as a supporting act, but after one performance the management had no choice but to make them the headliners, because their show and the audience’s response eclipsed that of musical comedy star Vivian Blaine, who, says Michael, “could not compete with the 40 minutes of madness from Martin and Lewis.”

‘Toast of the Town’

Radio gigs followed, triggering interest from the television networks, which, in turn, landed them on the first episode of Ed Sullivan’s variety show, Toast of the Town (which eventually became The Ed Sullivan Show), in June 1948. Their stay at the Copacabana was extended by three months, after which they traveled to Hollywood to appear at the acclaimed Slapsie Maxie nightclub. The audience there was filled with, among others, movie stars and movie executives, which (in the domino effect of their career) led them to several appearances on The Bob Hope Show, everything continuing to snowball from there.

On the Radio

In 1949, the duo agreed to star in their own NBC radio show, which would run until 1953. For them, though, it was a very different experience. Says Michael, “On radio, they had to stick to a script; at the very beginning they did not have any real creative control, although several of their catch phrases came from the show. Jerry at that point was already starting to look at Dean and go, ‘Are you for real?’ That became a standard line. But for that show, they put them into a situation comedy type of a thing where the two of them were aspiring nightclub performers and the plots would deal with them getting a new show together or going down to the studio to record something. There was one memorable episode because it was so badly written where Tony Martin’s fan club tries to sue Dean Martin for using that last name — it sounds funnier than it plays. The radio show had an interesting concept, it was just ineptly handled.

“At one point,” he elaborates, “they got into a very long story where where the two of them were going to buy and operate their own nightclub. That made for some interesting situations and they brought in supporting characters, but it was pretty obvious it wouldn’t last much longer. The show didn’t really build an audience, because it started before they made their first motion picture appearance — and even though it continued after their first film, My Friend Irma, where everybody started paying attention to these two. But mainstream America, the people who don’t go to nightclubs, still didn’t know them, so it didn’t build enough of a listening audience and the show ended up going off the air.”

Next Stop: Television

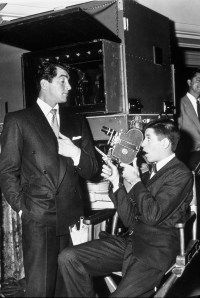

“In 1950,” says Michael, “The Colgate Comedy Hour was conceived and they became part of it. It was a show where a series of hosts would alternate weeks. Martin and Lewis made eight appearances during that first season — actually nine, because they also guested on a show that was hosted by Phil Silvers. They got the biggest ratings, because the show was just so much different from what the other hosts were doing. It was more freeform; Jerry didn’t hesitate to ad lib strange introductions to Dean’s songs, or he’d run around the theater and show the other cameras, or play around with the cameras. It was definitely something that the other hosts weren’t doing. And as I say, their charm is best appreciated when it’s visual; when you see all the physical activities that are part and parcel of their partnership.”

Times certainly were different. One can’t imagine today any celebrity being allowed to star in films, on television and yet another medium (in their case, radio) at the same time. “They were in such demand,” Michael details, “that NBC was willing to bring them back to radio just to keep them on the air. So they did a second radio series that lasted two seasons. It was written by their TV writers and played to their strengths. It was more of a variety show. Dean would come on as the ‘Master of Ceremonies,’ he’d sing a song, then he’d introduce Jerry. They’d do a little schtick and bring on a guest star, who they’d do a sketch with, and then Dean would sing again. All of it played better than the hackneyed plots that they were trying to deal with in their earlier radio show.”

The Big Screen Beckons

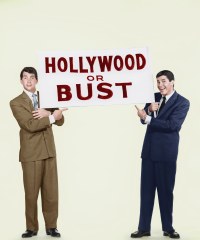

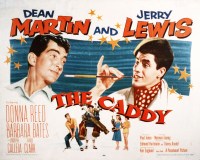

As noted, between 1949 and 1956 they made a total of 17 movies that audiences absolutely loved: My Friend Irma (1949), My Friend Irma Goes West (1950), At War with the Army (1950), That’s My Boy (1951), Sailor Beware (1952), Jumping Jacks (1952), Road to Bali (1952), The Stooge (1952), Scared Stiff (1953), The Caddy (1953), Money From Home (1953), Living It Up (1954), 3 Ring Circus (1954), You’re Never Too Young (1955), Artists and Models (1955), Pardners (1956) and Hollywood or Bust (1956). The success of Martin & Lewis on the big screen far eclipsed radio and television in terms of audience popularity, though from Michael’s point of view they were never as creatively formed in movies as they had been in other mediums. Ironically, it was that same big screen success that ultimately tore the team apart.

Ambition Becomes the Enemy

“Both men were ambitious,” Michael emphasizes, “and both men wanted to be successful, but Jerry wanted it to be more than that. As he later put it, he wanted to be the King of Showbiz. He wanted to learn how to produce and direct and create his own films. He was starting to envision situations where his character was more than just the crazy guy, he also wanted to be sympathetic. He wanted to be more of a ‘lovable schnook,’ which was how he originally termed it. And that played havoc with Dean early on — he was already beginning to sense that as far as their films were concerned. And remember, the films were going to be their legacy, because the thought at the time was that TV and radio were aired once and gone. Nobody thought about rebroadcasting kinescopes, because they only existed for one-time airing for cities that couldn’t telecast live.”

So it was their firm belief that the series of films they starred in would be what would stand the test of time. “But most of them,” Michael suggests, “were cut from the same cloth. Dean was the smooth sharpie and sometimes a real slimy guy. But then, after interacting with Jerry, who was the lovable guy and the funny guy, Dean would eventually see the light and by the last reel he would be the good guy and would help out with whatever Jerry was doing. It was the same formula time and time again, and Dean was getting tired of it.”

“He wanted to do something more ambitious,” he adds, “but he realized he wasn’t going to get that chance. And now that Jerry was bent on becoming a sympathetic character at all times, even on TV, he knew what was going to happen. He was going to end up playing the one-dimensional heavy who becomes nice in the last five minutes of the show. Like I said, he was getting tired of that. Also, he was beginning to make a mark as a singer for the first time with ‘That’s Amore,’ which was from their 1953 film The Caddy. That became a huge smash and was even nominated as Best Song for the Oscars. So Dean wanted to pursue more of that as well, and he wasn’t getting the chance to do that in the films, because the emphasis was slowly becoming more about Jerry and what Jerry was going to do in this situation and what Jerry was gong to do when something goes wrong and how he’s going to react to it.”

Essentially he was getting shunted aside, and Dean was well aware of what he had brought to their performances. Says Michael, “He understood just what his strength was in the act. He once said, ‘I’m the straight man. If I was jealous, this act would have folded years ago.’ So it wasn’t jealously, it was ambition that broke them up, and Dean didn’t want to work with a guy who was spending all this time up in the control room lining up shots, or telling the director what to do, or working with the musicians what their contribution was going to be. Jerry was doing all of those things for both film and TV. Jerry was trying to take over.”

“Jerry later said, ‘I tried to tell Dean that this is what we should do for our career and he didn’t agree with me and I was terribly hurt by him and what he did. But in retrospect that was wrong, I had no right to expect it.’ But at the time there was a great deal of bitterness between the two of them that just festered and eventually spilled out. You can see it happening when you’re watching their TV work later on. I tried in my book to put some context so that everyone would know, ‘OK, this is what was going on behind the scenes at the time their show was done.’ The thing is, the media did love Jerry. He was the guy who seemed to grab all the attention, the one who was swinging on the chandelier and the one who drove into a camera and knocked it over while it was shooting.”

“But the thing to remember is that while Jerry was the center of attention, Dean was just as enjoyable in the beginning and, in many ways, just as funny. It was just a different kind of humor and people got that. But the main reaction was to Jerry; he was the catalyst. As we discussed, in the films that was absolutely true. It was less obvious on TV, but it gradually became more obvious as Jerry became determined to play the sympathetic, likable character and not just the crazy guy with the handsome partner.”

Changing Career Trajectories

The aftermath of the dissolution of Martin & Lewis is filled with irony in that Dean’s career — both in terms of singing and acting — soared throughout the ‘60s and beyond, while Jerry actually began to struggle to find new directions for himself. Michael suggests, “Jerry was so in love with show business that he tried reinventing himself time and time again. You saw that when he did Martin Scorsese’s dramatic picture King of Comedy, and dramatic TV shows like Wiseguy. Then, of course, he became an elder statesman of comedy. But when his Paramount contract expired, he went over to Columbia and started trying to do more sophisticated humor, but was having a hard time finding his way. He was still going back to the idiot kid from time to time, because he felt like that’s what audiences expected of him.

“Meanwhile,” he elaborates, “Dean had become a very fine actor. And then, of course, he had his TV variety show, which really struck a nerve with people — it’s amazing how powerful television can be when it’s done well. On top of that, suddenly his records were selling better, because he was now plugging them on TV. And he was able to maintain his motion picture career while doing TV. So, yes, Dean was more visible, his films were better, because he was playing a variety of characters and doing them very well. At the same time, Jerry was falling out of favor and eventually, by the early ’70s, had stopped making movies altogether and his life pretty much went into the muscular dystrophy telethons.”

Final Reunions

Dean and Jerry had a number of brief onstage reunions over the years, the most significant coming in September 1976. That one was orchestrated by Frank Sinatra , who brought Dean out during the annual Jerry Lewis MDA Telethon. According to Jerry, this (combined with the death of Dean’s son Dean Paul Martin in 1987) was the spark that started them communicating on a fairly regular basis, though in his book, Dean and Me, he states that they spoke almost daily. “They made peace,” Michael concedes, “but a lot of that is Jerry saying what he thinks the audience wants to hear. When Dean’s son died in that tragic plane crash, Jerry came to the funeral; didn’t announce himself, just stood in the back, never made his presence known. He just happened to have been seen by Dean’s manager and the manager later in the day said, ‘Did you know Jerry was there?’ Dean was astonished and asked his manager to get Jerry on the phone. Dean had never called Jerry; Jerry had called him a couple of times, but this was the first call that he made. The two of them spoke for 20 minutes say some sources, though how long doesn’t matter. They made nice and after that Dean stopped making cracks about Jerry, even when he was just clowning around, and Jerry started his great push to portray their friendship as having been reignited with the stories about calling him every day. Whereas the reality was a much more casual thing, but at least there wasn’t the animosity.”

In the End

As is so often the case, looking back one has to wonder if all that animosity — whether dealt with in some capacity or not — was worth it. Dean died of acute respiratory failure resulting from emphysema on Christmas Day 1995 (he was 78), while Jerry died of end-stage cardiac disease and peripheral artery disease on August 20, 2017 (at 91). Their legacy separately and as a team lives on. Michael considers the latter, offering, “I closed the book with their own observations. Dean described their legacy as, ‘With Jerry and me, it was mostly just doing what we felt and it was a lot of fun.’ Jerry said, ‘It’s two guys who had more fun than the audience,’ and that’s how I feel, too. Watching them do their nightclub routines on The Colgate Comedy Hour or even in many of their sketches, particularly in the early years where the two of them are not taking it seriously and are ad libbing constantly, and making fun of the props and things like that, it’s a joy to behold. It’s so different and so refreshing. It’s anarchy slapstick and warmth just melded together into a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.”

No comments:

Post a Comment